|

16th October 2011

|

||

|

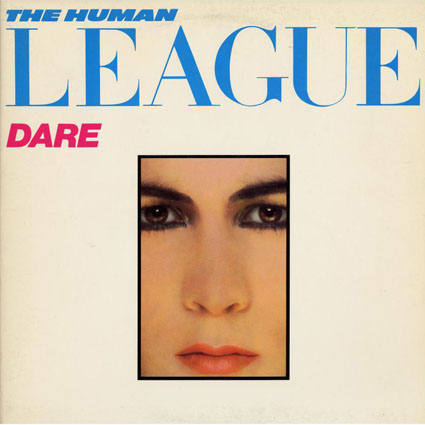

It's hard to believe it's 30 years ago that the ground breaking electro pop album Dare was released by Virgin Records (it also came as a surprise to several of the contributors to this piece), but it's true! I thought the best way to celebrate the anniversary was to drum up comments from as many as possible from the old team that masterminded this important album and let them think back to the time of writing and recording it. Martin Rushent was very eager and enthusiastic about contributing, but sadly never got round to do it before his way too early death. So this special is dedicated to him and his extremely talented knob twiddling that meant so much to so many people. |

||

|

Interviews by Niels Kolling, except Oakey by Simon Price (taken from the Dare 2007 Tour programme and used with kind permission from The Human League management). Jo Callis words on Martin Rushent kindly donated by Tim Rushent. |

||

|

Ian Burden; I didn't know it's been 30 years. Thanks for making me feel old :-)

I think the Dare album is largely the product of Jo and Philip, with me playing second fiddle and Martin Rushent taking command of recording in terms of schedules and engineering. Adrian wrote some lyrics and brought some charming one-finger ideas to 'his' songs. That was the team.

The girls were either recorded seperately in Sheffield, or at Genetic studios during their time out from school work.

Everyone associates music within the context of their own lives at that moment in time. When I hear the Dare album I see the interior of Genetic Studio, Martin chain-smoking and my occasional walks around the surrounding countryside and frequent dips into the swimming pool. It was a hot summer. Phillip Oakey; The joy of driving down to Genetic, which was out by Goring-on-Thames, swimming in the pool, waiting while Martin did the drum tracks, hanging around and living in Oxford, being free, and British summers. Oh, and getting on with Martin Rushent who was quite a Tory, and it was bizarre that we could get on so well. We're about as different politically as you can be. The reason I let Martin Rushent get away with it was that I was quite fond of a punk band called 999: I liked the sound of what they were doing with the vocals, although in fact the lead singer sounded like the silly one from Abbott & Costello. Plus I loved his work with Pete Shelley. So I already had records by him so I thought we'd give him a try. He'd always been an ambitious guy. He wanted to get a pure synthesizer thing going, give it a pseudo-scientific name, and really push it. For instance, he had something to do with Visage. Most of them were sleeping in his house for that first record. Pete Shelley's solo work was really good and maybe if we hadn't got in the way and taken the attention he would have been more acclaimed for it. We recognised that Martin would have the technical expertise to get the machines to do what we wanted. Because machines wouldn't talk to each other in those days. If you really wanted the drum machines in time with the bassline, that was beyond most people. We had these Japanese synths which were half the price of Moogs, and somehow, Martin Rushent made them sound like Moogs. We wanted novelty, and at just the right time things came into shops which delighted us. If you pressed that button there, it would make a sound you'd never ever heard on a record before. We were so lucky to be young at the right time to enjoy it.

Jo Callis; Didn't realise it was the 30th Dare anniversary coming up ! I did get involved in some of the BBC6 30th "Punk" anniversary celebrations back in 2006 when I was still in The Rezillos, and now it's the turn of the "Futurist"/"New Romantic" movements (never was too keen on those tags though). I guess it's all coming of age now.

I had been a punk, been a post punk industrial funkateer, so now at the dawning of a new decade of pop I had no hesitation in accepting an opportunity of involvement with moody Sheffield synth band The Human League, and become a New Romantic, joining the new popular culture movement that was sweeping the country in the wake of the underground popularity of pioneering seventies Euro-Techno music and Roxy / Bowie club nights held in every fashion conscious city and town the length and breadth of the nation. Well I thought, any excuse to wear make up and dress up like a lass.

It was always a pleasure to see Martin, whether at work or play, for work was like play and whilst at play, we would often talk of work - well, either that or listen to Martins relentless "pub jokes" all night. I was delighted when I heard the news that he was to be the producer of what would be the Dare" album. Martin would show great faith and belief in those he valued and encourage you to push yourself that little bit further.

Demo’s were recorded on The Human League’s antiquated Eight Track tape machine, with most of the synth parts being played manually straight to tape via the mixing console! The procedure for the recording of “Dare “ was that we would write and record rough demos of two or three songs in Sheffield, and then travel down to Martin Rushent’s “Genetic” studios for a couple of weeks where the final recordings would be made, with of course, Martin producing the tracks.

He trusted in what he saw as your abilities, even if you didn't quite see some of those abilities in yourself. You were always learning off him all the time without realising it - he even trained me into a semicompetent 'tape operator' (in the days of analogue reel to reel tape recording). He kept no "studio secrets" of his techniques, because he knew that any competent recording engineer could copy those, but what they were perhaps unlikely to have had was Martins feel for the entire studio and all of its connected equipment -as if it were an instrument that he could play and experiment with.

Martins attitude in the studio during production was almost like he were an extra member of the band, he did have to be boss of course, but listened to everyone's point of view, I think the girls in The Human League respected that he'd always listen to what they had to say, he knew that they were the kind of teenage ladies of the day who would go to the cutting edge clubs where this music we were making would hopefully be played.

He often walked the line between arbitration for the better ideas and keeping everyone sweet. He was very passionate about what he did and would generally work on projects which inspired him. His commitment would be equal to that of the artistes' themselves, so when he felt strongly about an issue things could get a little explosive.

Mr Rushent, you were, and still are, a great friend, mentor, kindred spirit and inspiration, along with a few other things I could probably mention. You have had a major impact on my life, as indeed you have had with many others. I am proud to have known you as both valued friend and colleague and in some respects even more so now as ever more of your stories and achievements come to light in the wake of your untimely and heartbreaking passing. .

So Brother, I'll have to catch you in the next life, cos I'm pretty sure I'll end up in the same place as you. And yet it seems as though you're still here, through that embedded connection you left with family and friends, and all the other lives you touched either directly or indirectly. And who could ever bloody forget you.

God bless you good mate. I know you will be getting deservedly praised and hailed yet again upon the 30th anniversary of "Dare", And I will certainly be raising many a glass to you.

Dave Allen (Engineer); Always hard to asses with hindsight. All the smart money was on Heaven 17. I loved what we were doing, not really though I was green, though I sang in my chains like the sea. Still sounds phat whenever I hear it out and about.

The most difficult song was Heavy Metal On 45 by the Terrible Lizard, which me and Jo (Callis) did at nights as guitars were banned. That was fun, because we were just pissing ourselves laughing, doing Smoke On The Water over a Linn drum.

I really wanna see Jo again. Bob Last liked him, learnt a lot from his tea making. Not joking either, he always made a rake of tea before he left the studio. Bloody Jimmy Rushent turning the electricity off and losing two days work, he was 4 or something. Bless ...when I see him next!

Went to Paris (on the Dare Tour 81/82), all the gear went wrong and it was awful, timecode slipped etc. Was also funny, especially the gay club that the record company chose for the aftershow, probably on the grounds that they all wore makeup. Martin charged me for the hotel room, so I had to invoice him for using my synth. Funny it came to exactly the same amount.

Being in the presence of greatness rubs off and gives you a bench mark for future work. Martin was a genius though, I was merely Sancho Panza. I owe Martin a debt of gratitude for the training, and the break. Thanks Mart.

Bob Last (Manager); I believed then that they needed a platform for the pop break- through I was sure was just around the corner for Phil.

I had worked with Jo as part of the Rezillos and come to revere his sure sense of killer chords and hooks (not to mention some bad ass guitar noise he could rustle up when called upon).

I was pretty sure he could reinforce the pop writing ambitions of the new Human League and that it could be interesting for him to have to rewire his process by laying his guitar down.

It was extraordinary to go all the way from the cassette tape in the post to a global number 1. Thing I remember most is a chaotic and very cool 72 hours in Reykjavik at the end of the tour at that time. Simon Draper (Virgin A & R); Once we had the hit with The Sound Of The Crowd and as the recording of Dare progressed, we all knew that we had a phenomenon on our hands and of course the prospects were extremely exciting. When the band split up, I was anxious that The Human League name should continue since it was clear from the reaction to the first two albums that something was building. But I must confess that I thought that Martin Ware and Ian Craig-Marsh, who were after all the only musicians in the band, had perhaps a stronger chance of being successful. I under-estimated Phil Oakey’s vision. The album was so outstandingly successful and have certainly stood the test of time. THE THINGS THAT DREAMS ARE MADE OF

Ian Burden; It was one of Adrian's one-finger ideas with Philip adding more one-finger ideas, and the lyrics are pure Adrian.

Phillip Oakey; It's a great statement, and it's one you can only make once in your career. It was great to say 'How about if we went round the world, and did all these great things?' And once you've been round the world, you can't do that any more. It would be (sings) 'Guess what we saw…'

It's entirely Adrian's song. Every word of that. But it was a lovely opening statement. So much music at that time was doom-laden and despondent, and here you were, putting your neck on the line, saying “No, here's the good stuff“.

It's pretty odd, because Adrian is pretty doom-laden and despondent. He was always the least likely to embrace happiness. I always remember, we'd be driving along in the van sometimes, and he'd say 'I hope this van crashes, I hope we all go over a cliff, and I'll be happy as long as I die after you lot.'

Dave Allen; In my dumbass way I worked out how to sync the Linn drum to the Microcomposer using an oscillator and trying to make one code look like the other, ridiculous.

OPEN YOUR HEART Ian Burden; A Jo Callis instrumental with lyrics and vocal melody added by Philip. Our first outing with one of his (Jo Callis) songs was less successful in chart terms, after Love Action (I Believe In Love). But working in the studio with him was an eye-opener in terms of chord progressions and song structures. I learned quite a few things from him -- and so did Philip. Phillip Oakey; Jo brought it in. He'd been a terrific guitarist. He'd never really played keyboards but we made him. And he walked in with this, and it blew us away. But I've never thought what I wrote took it where it needed to go. Which is why it got to No.6 and not No.1, cos I blew the chorus. The verses are fine, it all linked together OK, but I never came up with that great chorus: 'Open Your Heart' is not a great chorus. I grabbed it out of nowhere. It's meaningless. I don't really want people to open their hearts! I don't know if it was about us. I've always read a lot, and taken things from here and there. I thought I was this sort of… injured soul. Which I'm not at all. I played it to Glenn (Gregory, Heaven 17 singer), almost in a cruel way, because it was one of the best things I'd heard in my life. Jo Callis; Ironically, I had started to work out tunes on guitar, playing along to an early drum machine which had about six preset drum patterns.

Open Your Heart did translate better on the keyboard and I think we used the same drum machine with the same preset on the original demo which was done in the Leagues old 8 track studio in Sheffield.

THE SOUND OF THE CROWD

Ian Burden; Philip synthesised a drum rhythmn and I added the instrumental parts. I wrote some random lyrics so that I could sing the vocal ideas to Philip (because I don't like singing la la la etc). He wrote the chorus vocals, but kept my surreal verse parts. (Surprisingly!)

It was gratifying to hear that song on the radio. At the time there was no way of knowing whether-or-not the other pieces we were writing would amount to either less or more of that sort of success.

Phillip Oakey; It's one of the weirdest songs ever to be a hit. If you listen to it now, it's so jagged and noisy. But I think Spandau had done 'To Cut A Long Story Short' before it came out, which had a very similar riff, and we thought well, maybe we could have a hit after all.

It's some analogy of Ian Burden's which has to do with hairdressing. Literally, the words are about hairdressing and putting make-up on. Which he didn't do a lot of, himself. He wasn't particularly glam. But he seemed to have a fixation with how the mechanics of getting your hair washed related to your life.

Bob Last; it is a well known fact that I had real doubts about releasing this as the first post split single and Phil and I had quite a stooshie (Scots for a strenuously argued discussion) about it. It did though signpost the way. Simon Draper; It was Phil Oakey’s idea that I contact Martin Rushent to help sort out The Sound Of The Crowd. Martin came to see me at Vernon Yard (an independent label owned by Virgin Records) bringing with him a tape of a newly completed track from an album that he had produced for Pete Shelley. Throughout, he had used the new Linn drum synthesizer to great effect. This was very exciting because I knew that Phil would not abandon his firm commitment to record only using electronic instruments. And thus far the weakest thing about the recordings, was the rhythm (or lack of it). Here was an electronic drum that really sounded great. DARKNESS

Ian Burden; Don't remember . . . except for hearing it very loudly whilst reading a biography of Talleyrand.

Phillip Oakey; That's an Adrian lyric. It's as simple as being afraid of the dark. There's no extra level to it. It's 'scary things scare me'. We started doing it again a couple of tours ago, and it's a real joy.

Jo Callis wrote the tune, and everything he does is musical. Some people have got that. Liam from The Prodigy has got it, Jimmy Jam has got it.

DO OR DIE

Ian Burden; An instrumental piece of mine (much improved by Martin Rushent's production) and vocals and lyrics written by Philip.

Phillip Oakey; There's a little thing about the lyrics that hint at being sexy. I've always tried to make the songs a bit… sexy. Not in a very effective way: I don't think I ever persuaded people that I was. But the first line has got 'cock' in it, which I'm quite proud of.

We wanted to do a bit of an uptempo song, but it just kind of happened. We were never the kind of band who thought 'Oh God, we've left out the ballad.' A lot of 'Do Or Die' was dictated by using a Linn drum.

The coincidences that happened to make the career go at that point were so many, and one of them was that Mr Roger Linn invented a machine called the Linn drum, and all that trouble that we'd been having for two albums - you'd have a bass drum that would work well twice, then go wrong - ended, cos they were a doddle to use.

Everyone else was stuck in a rut of 'Oh, you shouldn't be using that on a record, it's terrible', but the day the Linn drum came into being transformed everything for us. Pick a tempo, press a few buttons and off you go.

GET CARTER

Ian Burden; Basic theme melody from the movie with Michael Caine. A solo performance from Philip, playing the tune on a Casio VL Tone. (My) favourite song, don't know why…

Phillip Oakey; As soon as we heard the Casio VL-Tone… I think I was going out with Joanne by then, and she drove me over to Rotherham or Doncaster where they had them in the shops, because they didn't have them in Sheffield. We were totally knocked out by it.

We never get credited for the fact that it was a film no-one cared about until we recorded that tune. I love that film. We had a strong sense of coming from the North, and Get Carter is brilliantly evocative of that.

The film was about Newcastle, people with Northern accents behaving in a way that's worth filming. You hear Roy Budd's tune when Michael Caine is killing his last victim on the beach. It's so bleak.

'Get Carter', 'I Am The Law', 'Seconds', that chunk of the album is miserable! Three songs of misery, death and society breaking down.”

Dave Allen;

Me and Phil had Casio VL Tones and to be honest loads, but I

can’t touch type or remember, lol. I AM THE LAW

Ian Burden; Totally Philip, but with a lot of help from Martin Rushent. (My) favourite song, don't know why…

Phillip Oakey; There really wasn't a Judge Dredd element. It was Judge Dredd, There was nothing else. It's some bits of Judge Dredd being sung at you.

One of the things that really changed my life was when I was working as a hospital surgery porter and I met a guy called Vernon who used to be a bouncer. He had a goatee beard and long flowing hair, and he wouldn't swear if there was a woman in the room.

He talked about being a bouncer, and he said he thought his job was to protect people who might be hurt by people having fights. Girls who had gone for a night out and didn't want their eye taken out by flying glass. And he changed my mind towards all that sort of stuff, a lot.

|

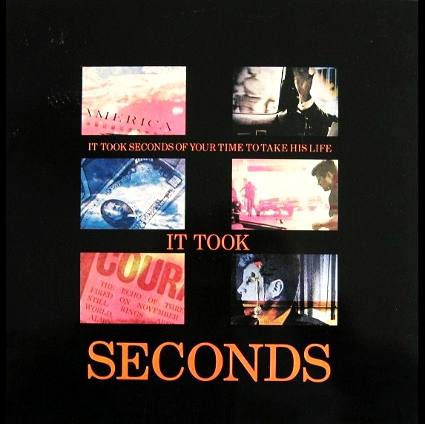

SECONDS

Ian Burden; Adrian's lyrics, and Jo Callis getting the synths to grind!

Phillip Oakey; It's Adrian's lyric. It's concentrated and focussed on… how would you get through that afternoon, waiting for him to turn up? The story for everyone is Kennedy getting killed, but the story for us is how do you become a person who can do that?

How do you spend hours, in a sweltering room, knowing you're going to try and shoot someone, and it isn't just going to change his life or your life, it's going to change the whole world. Even if I wanted to, I couldn't do it.

And it's about the atmosphere in that room. Adrian collected these bits of odd culture. He was fascinated by the interfaces between the media, celebrities, and the real world.

He was fascinated by Hitler, in terms of the way he could manipulate people. He probably saw the headline 'The Shot That Was Heard Around The World', and just took it. He was way ahead of his time. He predicted the culture of Hello! magazine before it came reality.

We put it on the B-side of 'Don't You Want Me'. It's the song that still knocks me out: 'Wow, how did we make a record like that?'

We started doing festivals a few years ago, and if we were down for an hour set, I'd say 'Right, let's start with “Seconds”'. We'd be in the dance tent, and everyone would be expecting us to start with 'Don't You Want Me', but we'd come out and do what was basically trance 30 years early. And we won them over from that moment.

Jo Callis; One of my all time favourites, even though I was "heavily involved". The song came out of a jam we had in the old 8 track Sheffield studio, which was quite an unusual thing in itself.

I was trying to imagine what The Sex Pistols might sound like if they were a synth band. I still love that rather dark, monolithic side to The League. And Seconds always sounded great blasting out in a club. Oh yes.

Dave Allen; Did most of Seconds on my own, (remember) pulling the sync lead out of the Linn drum at the end so that it went all wobbly

LOVE ACTION (I BELIEVE IN LOVE)

Ian Burden; My instrumental, and Philips lyrics. He'd have some odd bits -- like cat sounds and eccentric bits of percussion. I'd write an instrumental piece around them, arranged with space for his baritone voice and structured as a song. I'd hum him a few possible tunes and he'd go away and write the vocal parts.

I have a cassette tape of the demo we recorded in Sheffield, remarkably similar to the final version recorded with Martin.

Phillip Oakey; It's another one where I had verses of things I wanted to say.

I'd got myself really mixed up in romances by then. I'd been married, and not been as good to my wife as I should have been. I believe she doesn't care, but I do regret it. I sort of think I'd betrayed the institution of marriage, which at the time I wasn't bothered about.

I still think that marriage isn't meant for people like me, and yet I don't want to slap the faces of people like my parents, who were married for 60 years, who as far as I know never looked at another human being, and got through the aftermath of World War II with four kids, and lived in houses where there were slugs coming through cracks in the door…

And people like me come along and say 'Oh I'm gonna get married, oh forget it, I'm gonna get divorced', and I felt like I'd let everything down. So that was all going on in my head… and we needed a chorus. So we put a bit of Emmanuelle in it!

Jo Callis; A nice thing about The Human League was that on some songs one could have very little involvement other than perhaps laying on a synth line or helping programme a few drum patterns, so the finished results can be listened to quite impartially.

I very much like Love Action (I believe In Love), which was pretty much Phil and Ian. I find I can listen to this tune in the same way I listen to my favourite songs by other artists.

Dave Allen; Love Action (I Believe In Love) is still my favourite, I really enjoyed the whole thing, especially the rap bit. Remember Phil being very doubtful about about saying “this is Phil talking” which we (me and Martin) thought was ace.

DON'T YOU WANT ME

Ian Burden; Adrian had a simple tune which Jo syncopated and then constructed the whole instrumental elements around it. Philip wrote the lyrics and vocal melodies.

Phillip Oakey; I thought it was too clever. For some reason, very unusually, I came back from the recording and left Martin and Jo there, and when I heard it, I thought they'd made it too slick. The choppy synth sound is triggered by a guitar, and I thought that was very close to breaking our rules about no guitars. I thought it was a bit too poppy for us.

And again, we didn't have a chorus. Martin sent us into a room and said 'Right, you've got an hour'. I came out and I was a bit embarrassed at how simple it was, but I sang 'Don't you want me, baby?' and Martin said 'That's GREAT!' Which was very impressive. He knew about pop.

It's that song, peoples view of our entire career is focused on that song. I've been doing radio interviews and they say 'Oh, Phil, are you there? We're gonna come to you in a minute…', and I know what they're gonna play me in with.

Jo Callis; Adrian seemed anything but human as he mercilessly began to bombard me with the brain numbing ten note riff which was emanating relentlessly from the workings of his Yamaha CS15 synthesiser, the room began to spin and my head was swimming as I tried to fight down the nausea which was rising from the pit of my stomach.

Make it stop ... I must .. make it stop, if I could just think of a way to utilise the hellish riff, adapt it somehow into the beginnings of a song, then, at least I might be able to limit its duration to brief periods of say four or eight bars, perhaps put some spacings between the notes? who knows, given time Adrian could maybe even be persuaded to change the frequency and timbre of the sound? Oh God! the noise ...the horrible noise ..Yes, that was it, I knew what had to be done, it was my only chance.

Using a very diplomatic approach, on account of the fact that I was “crashing” on Adrian’s couch (man) during my songwriting expeditions to Sheffield, I suggested that the offending riff be arranged into a four bar phrase with a resolving note at the end ( B major I think it was) this being syncopated against a simple chord pattern forming the basis for the verse of a song.

I’d been hearing quite a lot of Latino type stuff by the likes of King Creole and Coati Mundi in the clubs that I’d been frequenting whilst on R&R at the time, so this was where my initial idea was coming from, the riff can be plainly heard on the finished recording of “Don't You Want Me” as a brass part in the verses of the song, playing along with the chord pattern I’d put behind it.

Now we were off and running, we had the very humble beginnings of the song; Four chords and counterpoint top line sequence, now we needed some rhythm, which was quite a tall order in these historic days of electro-pop.

In order to create a drum track one was usually faced with three options, the first being the analogue twelve step sequencer, which was not recommended for the faint of heart or the novice, the second was the preset drum machine of the type used for electric organ accompaniment, which was quick and easy but with the dilemma of “Which setting should I use? Bossa-Nova, March, Rock 1, Rock 2, Disco (always a favourite) ,Samba? Oh! decisions decisions”, or thirdly just sit back and wait a couple of years until Roland invent the TR808 Programmable Rhythm Composer.

With the unique abilities of “Dr. Rhythm” we were able to program basic Kick Drum, Snare and Hi-Hat beats all from the one machine, it was almost a resounding “Ya Beauty! ”, well at least until something better came along. Very soon a truly basic four to the floor beat was programmed up amid some cursing at Mr Roland’s new technological little marvel, then a bassline which owed more than a little to War’s “ Me and Baby Brother” tailored to the chords, and we had us the verse.

On a little bit of a roll by now, I tagged on a new four bar sequence of chords and bassline which seemed to flow quite nicely out of the existing verse, this became the bridge of the song ( “Don’t, don’t you want me, you know I can’t believe it when I hear that you won’t see me.” would eventually go the lyric to this part.) which would precede the build up to the chorus, the bass part I had originally written here ultimately became the leadline featured during the “intro” of the finished recording, it being replaced by a bass part similar to that of the verse, that was producer Martin Rushent’s idea, giving another “hook” to the tune.

At this point in the proceedings, Philip Oakey entered the fray. Upon hearing the composition as it stood thus far, Philip remarked that it fitted in with an idea for a song that he had had simmering in his imagination for some time, which was loosely based around the “A Star Is Born / Pygmalion” theme, lyrically speaking.

He immediately consulted his large notebook, which accompanied him to all writing and recording sessions, and we soon found ourselves with some lines of lyrics and another musical section to the song which married up nicely with the work already realised by myself and Adrian. Well, now the song was almost writing itself.

The final section of the composition which I came up with to kind of resolve the parts we now had, and which were flowing together very satisfactorily, was probably the most crucial, for although we did not realise it at the time this would become the chorus in all its drunken sing-a-long splendour.

This didn't become apparent to us until well into the final recording stage at Genetic Studios in leafy Berkshire when Martin Rushent said something to the effect of ; “ ‘Ere Phil, that’s yer chorus there that is, now bugger off an’ write some bleedin’ words for it.” Mind you prior to that, during playbacks of the track in progress, Martin, myself and studio engineer ( now producer) Dave Allen would sing along our own “ chorus ” to this part of the song, which I’m appalled to admit was of such a base and sordid nature that I could not possibly relate it.

By the time of writing “Don’t You Want Me” we had already done a few stints of recording at Genetic, and we had been picking up a few tips on how Martin did his Synth Brass parts, which were used to great effect embellishing the final arrangement of the song. So being young(er) and tres optimistic we thought that we’d have a bash at incorporating some of these type ideas into our little demo.

Well, unfortunately our relatively meagre facilities in Sheffield could not compete with the state of the Techno art kit such as Roland MC 8 voltage controlled sequencer, Linn Drum Machine (one of the first in the country) and Roland System 700 Modular Synth which Genetic boasted, and so our results were quite hilarious to say the least, but even at that they did serve to pinpoint suitable areas for brass enhancement.

The first thing to do was put the kettle on, then the work would begin. Yes, when it came to Rock ‘n Roll excess few came close to Human League tea indulgence. I myself got started with just a little sip from somebody’s cup of PG Tips, just to see what it was like you understand, but pretty soon I was on about twenty cups a day, and thereafter I’d be brewing it up myself and dealing full cups to the rest of the band. Crazy days and crazy nights man.

So the backing track to “Don’t You Want Me” was arranged and built up during the week, with everybody concerned under the influence of tea. First would go down a guide drum track on the Linn Drum, which would later be replaced by the final drum track complete with fills and so on, then the other parts, bassline, chord patterns etc. would either be played laboriously by hand, as we were all crap keyboard players, or programmed laboriously on the Roland MC8 sequencer with every note,step and gate time entered separately into the machine. All in all quite a laborious process then.

The one little personal victory for me however, was persuading everyone concerned that one of the sequences on the songs verse, for which a sound had been patched up on the system 700 synth, should be triggered by my guitar, I always took it with me - just in case. They all hummed and hawed and tried to cover their inherent fear of the axe with lame excuses, but after I’d performed a convincing though puerile tantrum they relented, I got my way and of course the end result was bloody great, both in giving the song a funky George McRae “Rock The Boat” groove, and getting a guitar used on a nancy synthesiser record.

He seemed to quite value my opinion on his work, so, as was often the case he would run the finished idea past me first, especially if it concerned a song we’d collaborated on. “Jo” he’d start, with a slight trepidation as to my reaction, “ What do you reckon to this?..... ‘ Don’t you want me baby, Don’t you want me whooooaoh, Don’t you want me baby, Don’t you want me whoooaoh!’ ”.

Well, at first I thought he was taking the piss, but within a couple of seconds I realised the true genius of it. Phil’s simple solution to the problem was absolute pop brilliance, adding an element that would take the song to a not yet envisaged level. Sorted!

Perhaps he thought that the stark reflective tiles would provide an ambience befitting his performance, maybe the solitary isolation would help precipitate the laconic disposition that the delivery of the lyric required, perhaps he just liked the smell of toilets. It could have been for these or any other reasons, but as far as I was concerned he was out of every ones sight and way too close to the tea stash.

Dave Allen; Don’t You Want Me was Jo (Callis), Martin and me for a weekend while the rest went back to Sheffield. It’s a pity I don't have my polaroid of Phil singing in the ladies toilet, because that was funny. Phil has the photo, I gave it to him as it was a fuckin’ cheeky thing to do.

Bob Last; I was sure of from the very beginning of the Dare sessions that Don't You Want Me's opening bars were the beginning of a pop classic. Simon Draper; At the time it was beginning to be understood that only by achieving multiple hit singles from an album could you achieve really massive album sales. Don’t You Want Me was always going to be the biggest hit (it was this song that convinced Jerry Moss to license the Human League from us for America).

Parts of the interviews with Ian Burden, Jo Callis, Dave Allen, Bob Last and Simon Draper has been published on this website before and can be read in full by clicking on their names.

Sadly the great Martin Rushent didn't get to comment this piece before passing away, but you can read the interview he did for this website back in 2008 here, and you should also check out his awesome article in the Sound On Sound magazine where he goes into details about the making of Don't You Want Me, which can be found here.

The re-mastered CD edition of Dare can be bought here. |

|